People have seen online piracy as a victimless crime for decades— which couldn’t be further from the truth

By Hannah Mercanti

Did you know that in 2022, 22.4 per cent of Canadians committed an indictable offense? It’s true— despite our reputation as toque-wearing, maple syrup-drinking sweethearts, nearly a quarter of us accessed online pirating services.

Digital piracy refers to the illegal copying or distribution of copyrighted material via the Internet. Uploading movies and TV shows to sites like Fmovies or the now-dead Soap2Day, downloading your favourite song from Youtube to MP3, or posting a stolen PDF of a book to an online forum are all actions that could, realistically, get you arrested in Canada.

People do claim to have their reasons, though. It cannot be ignored that a large chunk of people simply cannot afford to pay rising subscription rates- the cost of living is consistently increasing in Canada and if someone wanted to subscribe to Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime, Spotify and Audible, that would add up to a total of $49.91 a month. That’s a pretty significant chunk of money in today’s economy.

On the other hand, some believe that companies already have enough of our money; some do it to avoid giving money to companies whose business practices or ethics they don’t agree with; others are just trying to save as much money as they can. Some, though, just don’t think online content is worth their money and download pirated content for free based on principle.

Regardless of the reasons people present to validate their habits, there seems to be a consistent debate about the ethics of the practice online.

It is quite literally a never-ending back-and-forth— if you search “pirating books” on TikTok, the first two videos are in direct opposition to each other. One is brightly captioned, “Why pirating books is OKAY!” while its counterpart reads, “Stop pirating books. It directly hurts and affects authors.”

In Canada, anyone who commits piracy is, according to the criminal code, “guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for life.” So why are there TikToks and Reddit boards about it? It seems that regardless of the fact that it is punished like other forms of stealing, lots of people online don’t see it that way.

Online pirating, as we know it, began in the ‘70s and ‘80s during the boom of technology and computers. Users figured out how to copy and paste and were suddenly able to share mass amounts of information with the click of a button. “That was radical, right?”, says Kavita Philip, an author and a professor of English at the University of British Columbia.

Pirating is unlike any other form of stealing, notes Philip. When someone pirates a book, that book doesn’t cease to exist- the publisher and the author have not actually lost it. “If I take your car, you don’t have your car anymore,” says Philip, “but if I download the specs for your car, you still have your car and you can still drive it to work.” This was what led some members of the tech community in the ‘70s and ‘80s to argue that it was essentially a victimless crime since it appeared as though no person was actually being deprived of anything.

This led to an anti-authoritarian, utopian attitude within pirating groups. According to Philip, many of the people in these communities felt that they should not have to pay for the privatization of information and that knowledge and information should be open and available to all. Community members felt that corporations had gone too far with copyright and IP (intellectual property) laws and felt vindicated in stealing content.

Take for example the case of Aaron Swartz, which Philip notes. Swartz liberated articles from JSTOR under the pretense that information should be available to all— he was subsequently arrested, and made a hero and martyr in the hacktivism and pirating community. “Again,” says Philip, “the utopian impulse behind the copying and sharing communities is that everybody should have access to that knowledge.”

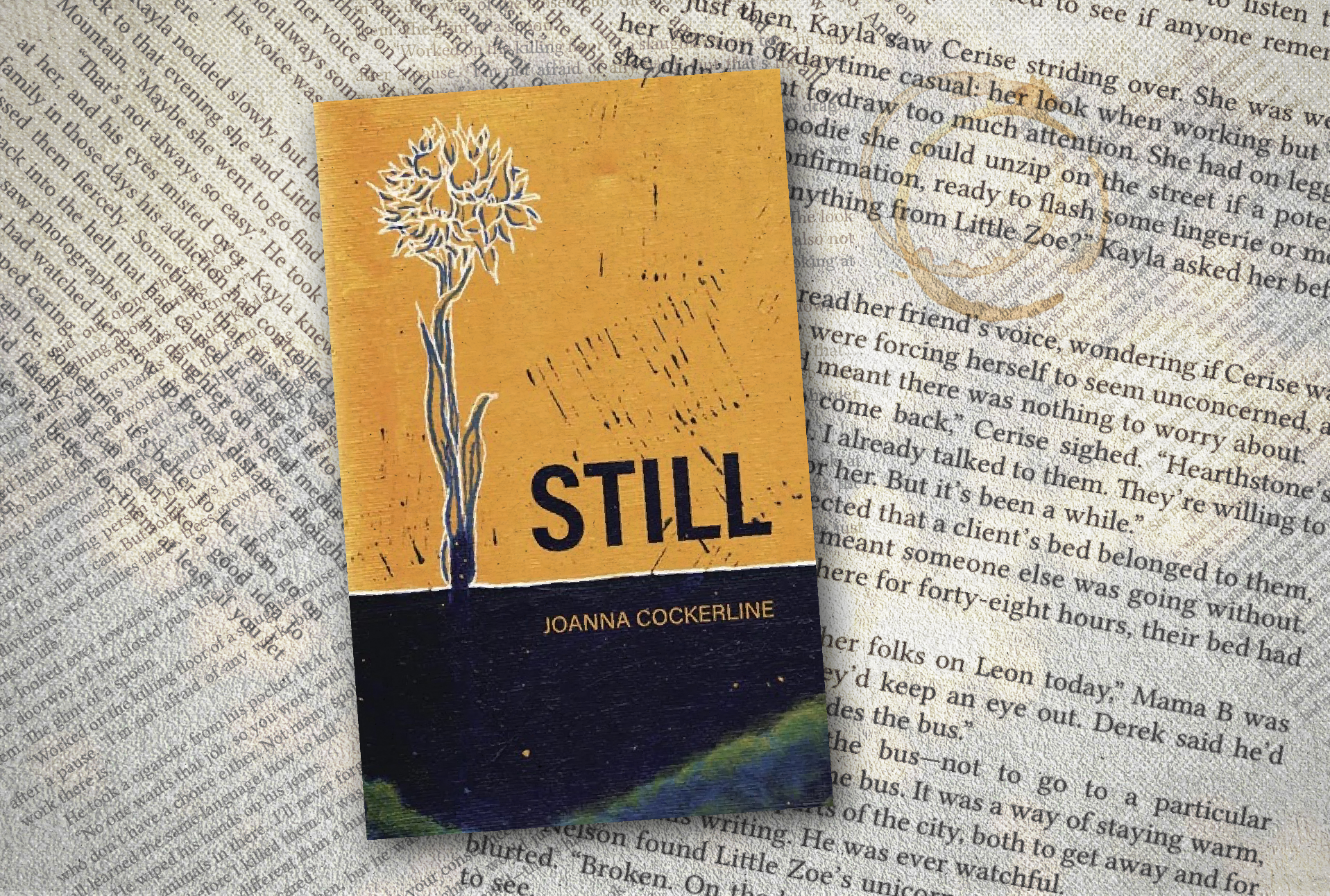

Part of the reason people are so readily willing to commit media piracy is because we assume that since there is so much media, we aren’t hurting anyone by taking it. “That’s actually not true,” says Brianna Wiens, an assistant professor of english language and literature at the University of Waterloo. “There’s the assumption that consuming more might actually help an emerging artist or contribute to them getting more airtime,” says Wiens. “Actually, pirating can be particularly devastating for emerging artists.”

When content is downloaded or spread online through hidden files, the artist loses a significant amount of exposure, since there is no way to track who or how many people are interacting with their content. As well, Wiens notes that downloading shady files in an attempt to skirt a fee can potentially leave the user vulnerable to online attacks and malware.

The fact that we are deep into a cost-of-living crisis does not help. People have less money now, and when faced with the choice between paying your Netflix subscription or buying groceries, the decision is kind of already made for you.

But, that doesn’t mean the answer has to be piracy. Wiens points out that as much as we are in a cost-of-living crisis, we are also in a crisis of the arts. “They’re not as valued as other kinds of technology forward or STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) forward disciplines are,” she says, noting that people may be less willing to pay for movies, music and TV because they see them as inherently worth less than other services.

They may also think companies already have enough money or have poor business ethics and believe they are doing something positive by sharing content and providing information to those who cannot afford it.

But, this argument, when de-constructed, doesn’t actually seem to hold up very well. Wiens points out that when people pirate content from the creative industries, the people doing the actual creative work are the first ones affected, not the ones at the top of the company. For example, if you pirate the latest Disney movie because you think the CEO is a terrible person, you won’t actually be hurting the CEO- you’ll be hurting new, developing artists, filmmakers, and writers since they are typically the first to go when companies start to lose money.

“It means less work for developers, testers, sound engineers, filmmakers, actors, scriptwriters, you name it, whoever’s involved in that process. It means less money going to those folks,” says Wiens. The issue, she points out, is that companies are not a monopoly, and looking at them like one makes it harder to see how something like pirating affects individual people.

Though, this doesn’t negate the fact that information should be free and made readily available to us. For Wiens, the thing that is missing in these piracy circles is advocating for our public libraries. “They don’t just lend out books. They also offer media and technology. For those who can’t afford to pay for video streaming services, your library will. Your library wants to help you.”

So, what can you do if you’re strapped for cash and want to consume media, but don’t want to hurt anybody or destroy your computer in the process? There are actually a couple of options.

As Wiens pointed out, the library is usually your best bet. The Toronto Public Library system offers movies, TV shows, audiobooks and ebooks for rental, all for free. But for readers who may not want to get up off the couch, there are a couple more courses of action.

Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive are two examples of free, online services with thousands of books uploaded for anyone to access. The only drawback with these two is that the majority of books are allowed to be uploaded because they have entered the public domain, so most novels available are quite old.

There is also the option to sign up for free trials, which most streaming services offer- though this option isn’t too sustainable, since they tend to last only a week or so.

So, maybe it isn’t the pirate’s life for us. The anti-authoritarian, utopian view of the early pirates does hold some weight. Information is something that should be free and available to all, no matter your income status or ability. However, fighting fire with fire is not the best solution and only hurts the artists we love and aim to uplift. By working a little harder and reaching out to our community resources like libraries, we can assist in the continued funding of the arts and hope for accessible and safe consumption of media for all.