Hayao Miyazaki’s directorial return presented to the audiences at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) the auteur’s love letter to his previous works.

By John Vo

(Courtesy of TIFF)

When Studio Ghibli comes to mind, the image of the man who sought to create more than films, but the most magical and immersive worlds, is formed. We think of the countless films created since the studio first came to fruition four decades ago. Yet before he solidified himself as one of the most prolific auteurs in not solely animation, but also cinema itself, Hayao Miyazaki was once a Japanese boy who longed to bring bold artworks and imaginative concepts to life. When 2013’s The Wind Rises came out, and Miyazaki himself claimed he would be retiring (although he already said that four times prior), many, including myself, truly believed that we wouldn’t be seeing more works from the movie legend. Until he finally shared the triumphant news in 2021 that we would be getting another film from him. That film would be the now-released The Boy and the Heron (or Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka).

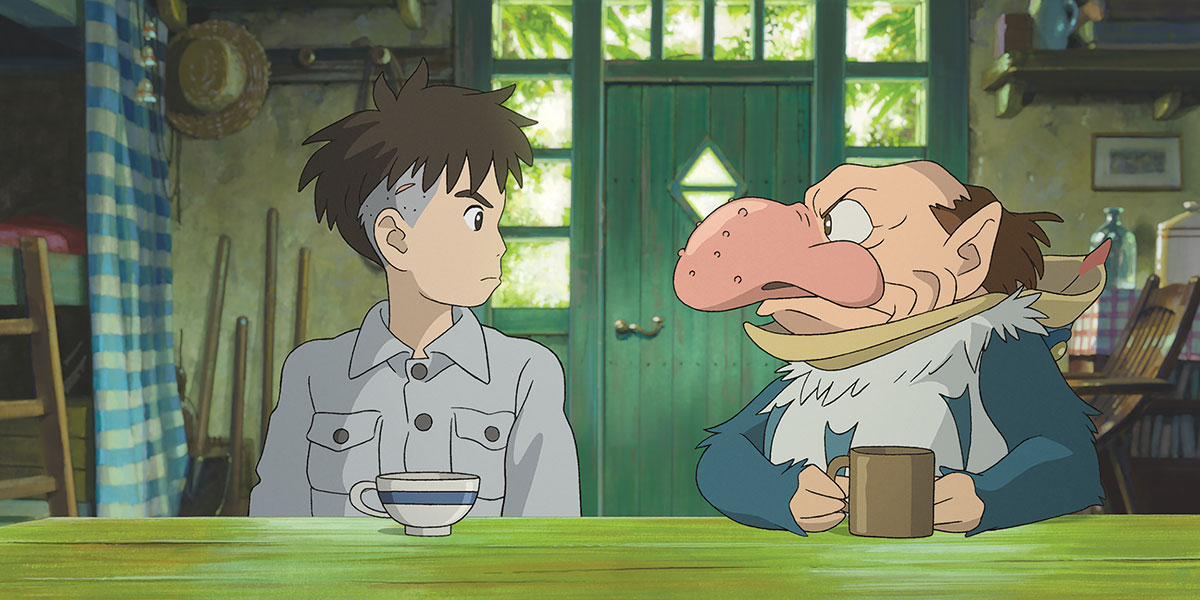

Very loosely based on his connection to the Japanese novel How Do You Live? by Genzaburo Yoshino, Miyazaki’s film is comprised of an original story and new characters. During the Second World War, 12-year-old Mahito loses his mother after a bombing that causes the hospital where she resides to burn down. His father soon remarries his late wife’s sister and the two move to another city in the country. As he struggles to adapt to the continuing grief of losing his mother and being in a completely new setting, Mahito meets a talking heron who tells him that his mother is still alive. Eager to discover what this strange and magical heron means, he follows him into a nearby abandoned tower and is transferred into a new world. Mahito then sets on a journey full of fantastical creatures and dangerous obstacles to find out what truly happened to his mother.

Although this synopsis sounds very straightforward, Studio Ghibli films have the innate ability to turn a simple concept and expand it beyond the scope of what anyone could’ve imagined; Miyazaki is not like any other artist. Before becoming an auteur, he was once just a boy in Japan during the bombings and remembers the brutality of war. His family and he would also face hardships, like when his mother got spinal tuberculosis. These key moments of his life are translated into the motifs in the projects he has helmed for Studio Ghibli. From his anti-war stances in The Wind Rises and Howl’s Moving Castle to how humans deal with illness and grief in films like My Neighbour Totoro, Miyazaki infuses the experiences of his youth into relatable and honest coming-of-age stories that portray adolescence as both the wondrous and arduous. The core belief that art can be used as a means of dissecting and understanding one’s emotional and personal turmoils is beliefs is ever so evident in Miyazaki’s body of work.

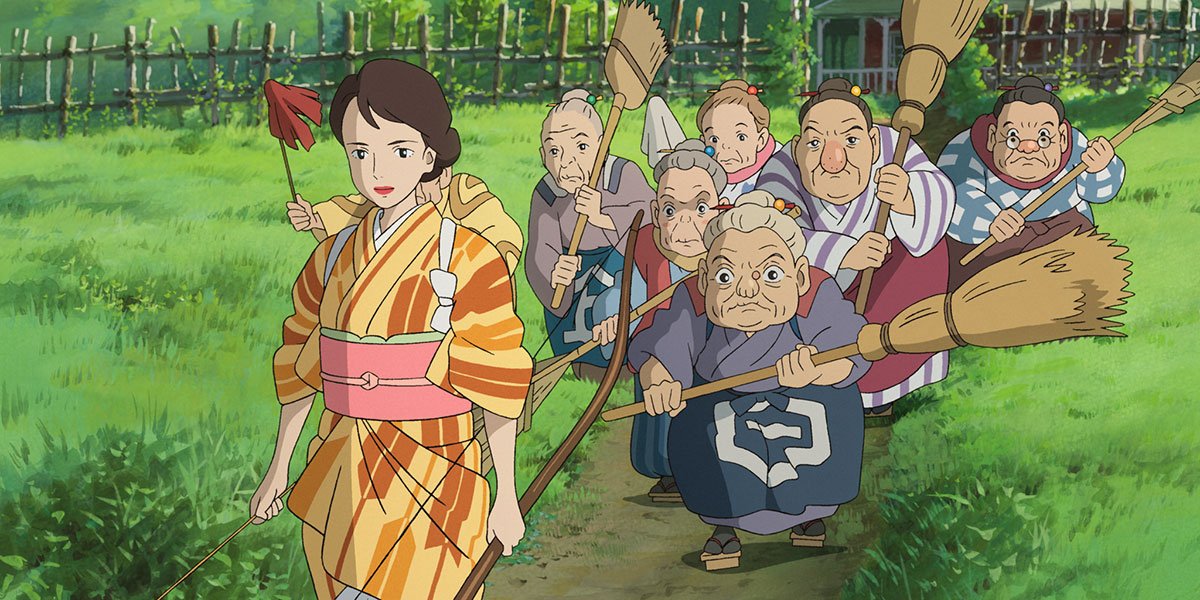

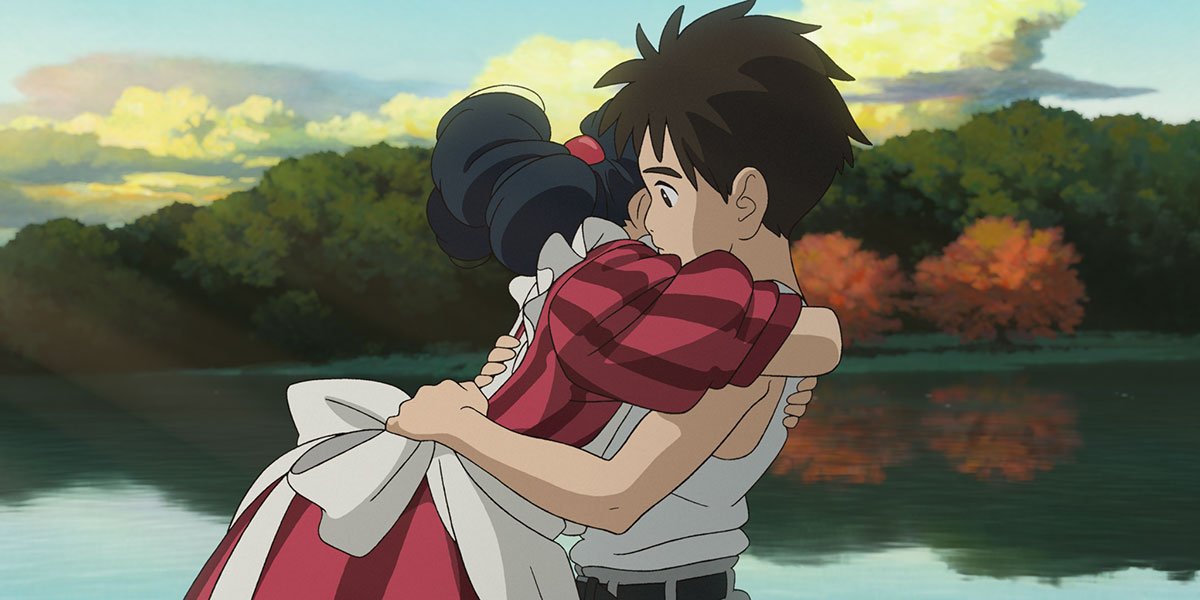

The Boy and the Heron is the amalgamation of everything you could imagine for a Hayao Miyazaki film and more. Cute creatures that would make adorable stuffed animals? Check. A fantastical world with its own set of physics and features? You got it. Another score produced by the mind behind the music of Ghibli, Joe Hasaishi? The closest thing one can get to an out-of-body experience. The animation? Oh, there are no words worthy enough to describe how vividly immaculate this film is to look at. The lush colours Ghibli loves to use in all of its films are present and paired with the iconic stylized designs of the characters and settings. When viewing the film, you’ll catch what will go down as one of the studio’s visually striking scenes, the animation becomes eerie and akin to how one might see a nightmare play out. It shocks you to the core but adds a whole new dimension to the film and the potential of 2-D animation. In our current climate where the only animated films you can catch in cinemas feature 3-D anthropomorphic animals just for the sake of a cash grab, Studio Ghibli and the Japanese animation industry as a whole are a firm reminder that 2-D animation is anything but a relic of the past.

At the heart of our story is a young adolescent struggling to adapt to the newfound changes in his livelihood and familial relationships. The character of Mahito acts as our eyes and ears into the countryside and the world he and we are about to experience. The dynamic between him and the other characters, especially between his father and former aunt now step-mother, are some of the most nuanced and complex relationships in the Ghibli canon. Yet, no character is written to be a two-dimensional caricature but are all provided glimpses into their viewpoints and what motivates their actions. We can’t mention a film called The Boy and the Heron without mentioning the titular heron. Although I only screened the Japanese version at TIFF — meaning no commentary from me on Robert Pattinson’s voice acting — the heron in the film remains one of the studio’s oddest secondary characters. His motives are shrouded in mystery for a good portion of the film and it is not until later we discover his true purpose within the narrative. The heron does lead to another point that the Japanese voice actors did an exceptional job with the script. Voice acting in animated film is nothing like acting for the cameras and the ability to express the character's words without being over-the-top is crucial. Like every past Miyazaki film, the voice acting is top-notch with moments of the subtle and dramatic interspersed.

Beyond the surface level and aesthetics, the consistent themes and storytelling of Miyazaki’s work are displayed at possibly an all-time best. Through the hero’s journey, the concepts of grief, violence and coming-of-age are explored in an allegorical manner akin to films like Spirited Away and KiKi’s Delivery Service. Although the film is set in 1940s post-WWII Japan, the themes of war and self-discovery are meticulously written to retain timelessness and relevancy to our current society. Now more than ever, Miyazaki’s clear stance on how war can affect countries as a whole and the youth affected mirrors current events today.

When fans of films, especially Canadians, discovered that the film would be premiering as the opening film for the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), it solidified Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki’s place in cinema as a trailblazer. His work has gone on to be referenced in games, and live-action works and is a key influence for other esteemed film professionals. It was so obvious even walking alongside King St. W where all the magic was happening at TIFF. The film became the first ever animated and international film to open for the festival, Torotonians lined up hours early for the special merch pop-up and for the small possibility of snagging last-minute tickets to see the film. Suffice it to say that the videography of Studio Ghibli means a lot to general audiences and film as a whole.

A swan song (pun half-intended) to the works of Studio Ghibli’s past, Hayao Miyazaki blends all the things audiences love about his work and creates a film that pays homage to the classics while standing on its own as a formidable film. The Boy and the Heron is a love letter to all the fans who look towards his films and animation as a source of inspiration and solace. Although the story will not be the easiest to understand once you exit the theatre, you leave with the same breathtaking awe and wonder that comes after watching a film of such calibre and raw passion.

The subtitled and dubbed versions of The Boy and the Heron are in theatres now. For more information or to buy tickets, check the link here.

Images courtesy of TIFF