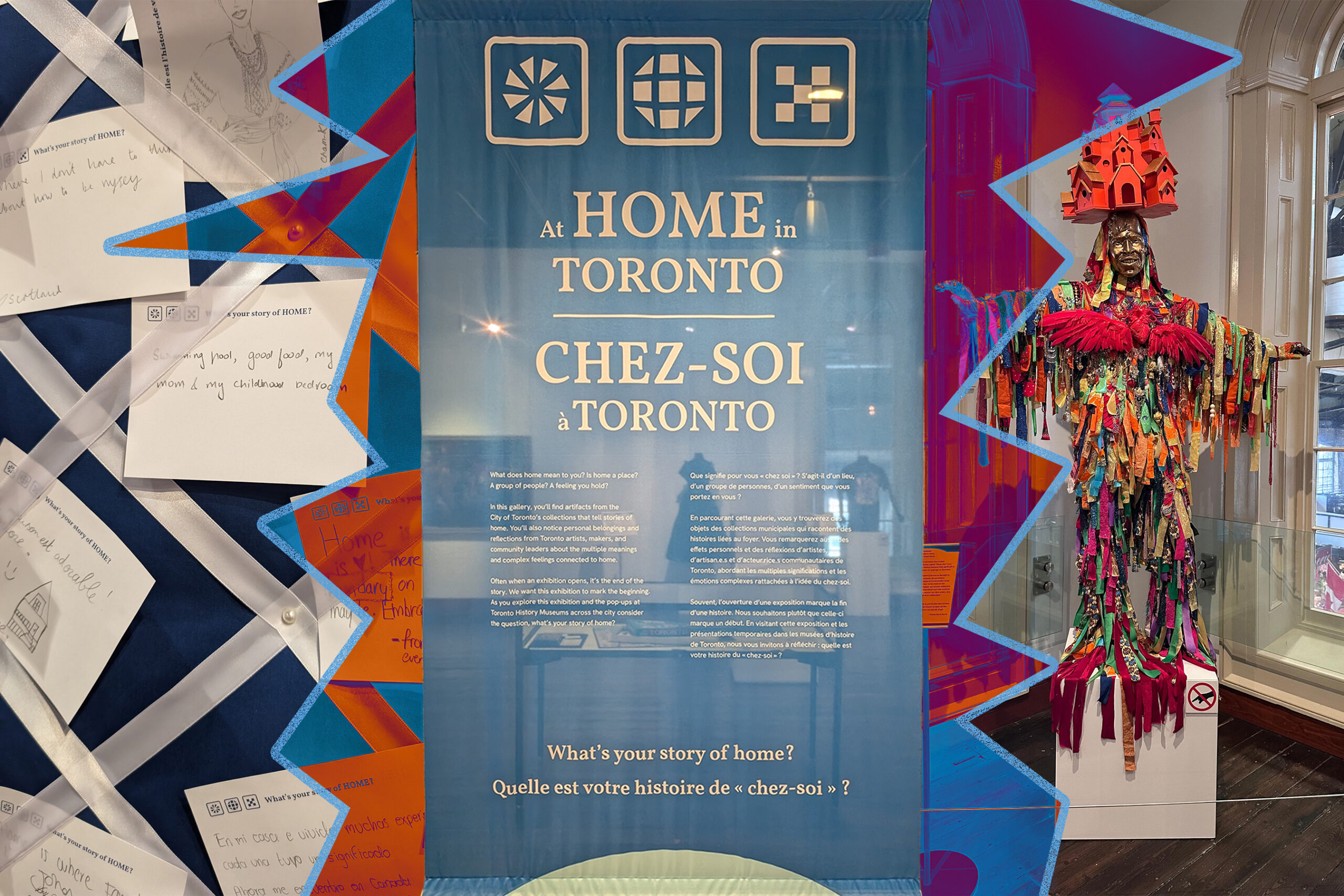

Bonafide collective is challenging traditional art spaces by incorporating live performance and obscure displays

By: Alexa Fairclough

Organized Chaos featured performance by pole dance artist, Madison Evoy (Courtesy of Chinelo Yasi)

With each new generation of artists and galleries, a familiar double bind appears that sees youth surpass the confines of institutional art. From the same age-old tension between the new and old that beget Monet’s impressionism, Picasso’s cubism and Duchamp’s ready-mades, Bonafide was forged.

Bonafide is the collective love child of four young, artistic, queer women curators in Toronto. Their first ever show together, Organized Chaos, debuted in a former Curry’s Art Supplies on Queen St. W. on March 10-11. Organized Chaos hosted a wide array of artists from traditional painters to installation artists, photographers, performance artists and DJs. One could watch a painting, be exposed to the scent of fresh paint and witness the very creative processes that lead to great art.

The future of Bonafide knows no bounds. This young collective shows that the Torontonian culture is immersive and has the possibility to be expansive. The atmosphere of the event intensified as time passed and the audience grew. Though it was a gallery space, it still had the same atmosphere of a party. The electronic dance music added an ambiance to the event that engaged the senses and made one feel as if it wasn’t daytime in a residential area. Alcoholic drinks were available to purchase, which only enhanced the night-life feel. With each new artist, a vignette into a different world was opened, yet there was still a cohesion throughout the event. As the theme of the show was revealed in its title, Organized Chaos, it was up to the individual viewer to decipher the images that they were viewing.

Canculture writer Alexa Fairclough met with the curators to discuss the creation of Bonafide’s debut show, Organized Chaos. The four curators, Sarah-Emmanuelle Ruest, Halle Hirota, Erika Lindberg and Jahliya Daley, work full-time while following their dreams. In terms of roles, they have an egalitarian ethic that encourages responsibilities to be equally among the collective. Artists themselves, Hirota and Lindberg had work on display in the show. By day, Ruest (Guelph ‘19) is a freelance producer, Hirota is a multimedia artist, Lindberg (McMaster ‘19) is director of communications at Underscore Studios, and Daley (Laurier ‘21) is a media and production specialist at Underscore Studios. By night they are the curators of Bonafide.

Artwork by photographer Kirk Lisaj displayed at Organized Chaos (Courtesy of Chinelo Yasi)

Get to Know the Curators:

How did Organized Chaos come to be?

Lindberg: We wanted to create a new experience for people who haven’t had access to displaying their work in professional spaces. We want artists to feel like they are gaining something and not that they are being taken advantage of. This space is meant to encourage the artist to sell and showcase their work.

Ruest: Halle and I have worked together in the past and ran an event after COVID-19. It was a huge success as everyone was eager to be out after being in the house. The goal of the show is to allow artists to display their work free from financial barriers.

What barriers did you face?

Lindberg: We worked with the venue owners before and got the space without financial constraints. It’s hard to establish a gallery that is diverse and intersectional in the art forms people are used to in traditional galleries.

Ruest: We use ticket sales to cover expenses that they cannot afford in the first place. It was really hard to get grants and partnerships from the government in a short time frame; it’s really hard for young artists to find funding.

Hirota: Time and energy. The bylaws in regards to having a gallery and party space in one. We want it to be a family-friendly space, but we have pole dancers and DJs. We want to change the way that art is experienced and how people create.

Where did the creators come from?

Hirota: We pulled from our immediate community because it required trust.

Daley: Social media also played a very big role. It connected us with future artists based on what we see from others.

Do you feel that your artists reflect the diversity of Toronto?

Ruest: To an extent. It’s hard to ask others to be a part of something without the money.

Lindberg: With limited financing, we needed a network of people that can be trusted and we were heavily reliant on favours. The point of this is to be able to grow funding.

What does this experience mean to you?

Hirota: So much. The start of an era.

Lindberg: People deserve to have great access to art. We want people to have a positive community in Toronto. We want people to feel that they can succeed at home. Community does not have a space, it is a feeling.

Ruest: We want to create more access for people to get paid or recognized for their work. It’s beautiful to see artists come together and work with each other. We made a gallery that is about community versus one person’s space. We don’t want Toronto artists to feel like they have hit a plateau and then go abroad. Where is the feeling of support/connection abroad?

Daley: It’s a tangible thing that came from the community. There’s a sense of love in coming together, truly.

What does the future hold for your collective?

Lindberg: More activation and bigger reach.

Hirota: Our main goal is to pay people for making art and to expedite the process of getting paid for art.

Ruest: Two activations in ideation for April. We’re planning an indoor/outdoor collaboration hopefully with the City of Toronto. We also want to reach untapped artists. Most importantly, we want to allow people to be able to create what they want for money.

Get to know the Artists:

There were quite a few immersive artists featured at the exhibit including Joy, an Egyptian experimental computer and performance artist who submitted both an immersive art piece and a pole dancing performance to the show. Joy’s immersive piece in which a musical keyboard — with each key corresponding to a different image projected onto a screen, rather than a note — invited viewers to challenge their conventional notions of which senses should be engaged when using a musical instrument, bringing together the visual and the tactile. As more and more keys were pushed, images continuously overlayed each other in an excellent work of media.

Although Organized Chaos transformed the way art could be displayed, there was still a section that adhered to tradition.

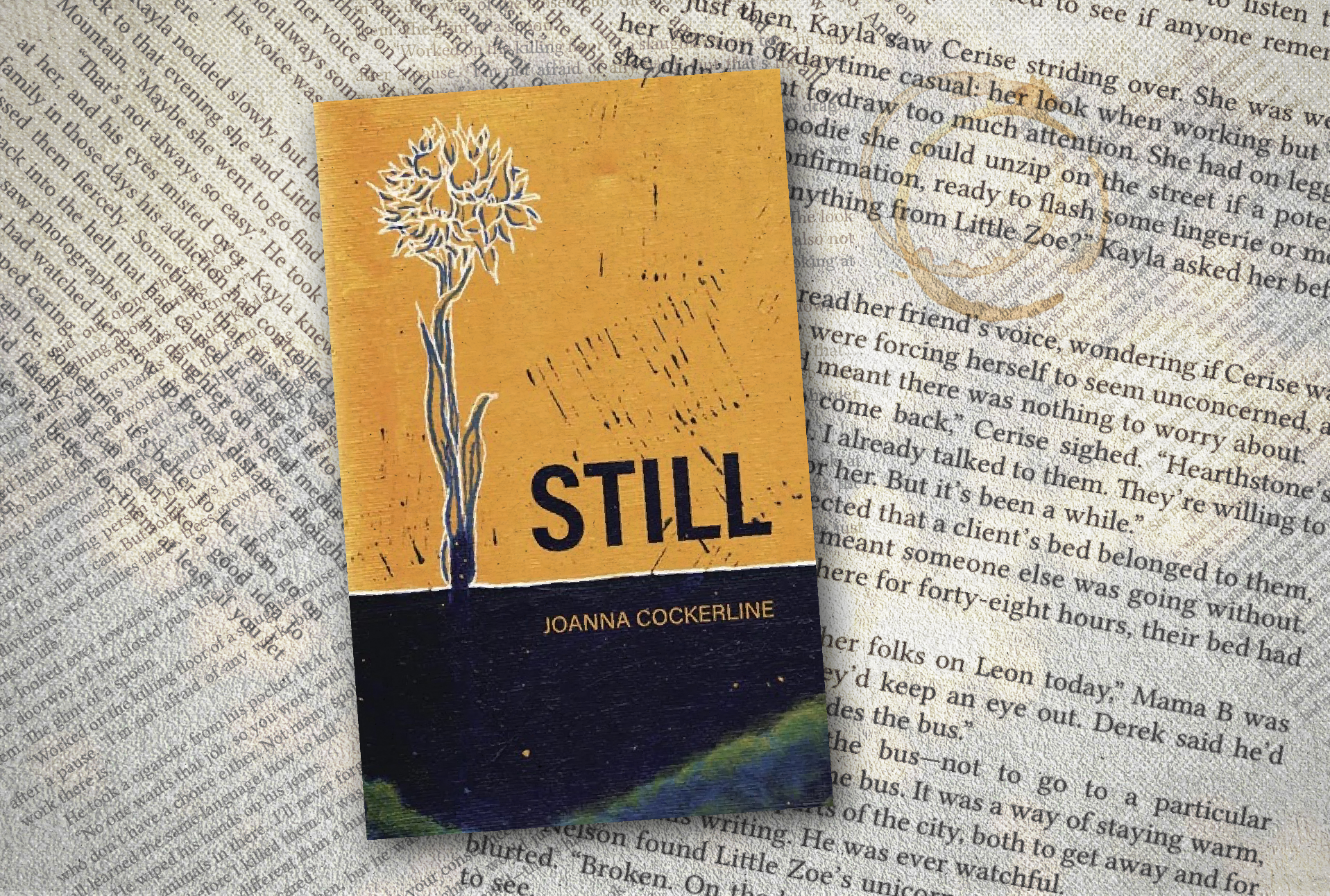

Artwork by painter Daniella Williams displayed at Organized Chaos

Daniella Williams (Guelph ‘19) is a contemporary figure painter. Her display at Organized Chaos contained painted vignettes that allowed the viewer to peer into the daily lives of everyday citizens, rather than the often noteworthy figures exhibited in traditional settings. Her work was detailed, yet elusive, thanks to her ambiguous broad strokes that left the faces of the subjects vague. This allows the viewer to imagine themselves or people that they know in the piece. She displayed couples spending quality time together, families at the beach, sweet memories that remind the viewer of happy days and spending time with the people that they love.

There was also a mixed media piece by Lxyxt (pronounced Light), a multi-media artist who explores decolonization represented by RAW artists — a network that provides independent artists with local and international exposure. Floating sculptures seemingly defied physics, a welcomed alteration on the way one traditionally expects to experience art. The heavy objects floated in the air and told a story that started in the skies and continued to the floor. The sense of movement conveyed by the works was magnifying — not only do you need to walk around in order to get a sense of its magnitude, but the aerial proportions added large amounts of spatial depth that truly transcends the piece and the gallery space as a whole.

As for the art of performance, Lou Rouse used her entire body as a canvas and even worked in an outfit that appeared to be made out of canvas, utilizing her corporeal self to create an ephemeral art piece. In a performance piece filmed by video creator Grae, Rouse flitted throughout the piece, applying pressure to the canvas to deepen her marks, and flowed melodically to the music.

The artist appeared to be in a total state of Zen as she made her mark on the canvas with every tool she had — even those not conventionally used to make gallery art, like her body. Her work conveyed the message that the body is art and art is within us; it is not something that can be segregated from the human experience. Even on a less hyperbolic and metaphysical level, she said we do not need anything outside of ourselves to enrich our lives, a message that is seldom conveyed in an era where mass commercialization creates ads out of everything.

Organized Chaos was a show for everyone, collectively constructed by every type of artist. The four co-curators came together to create a sold out show which was visionary in nature. It brought together both performance and visual arts, making the attendees stop and ponder how these two cohesive forms of creation could have ever been segregated. If you didn’t happen to catch this event, do not be dismayed; while Organized Chaos was one of one, Bonafide has just begun.