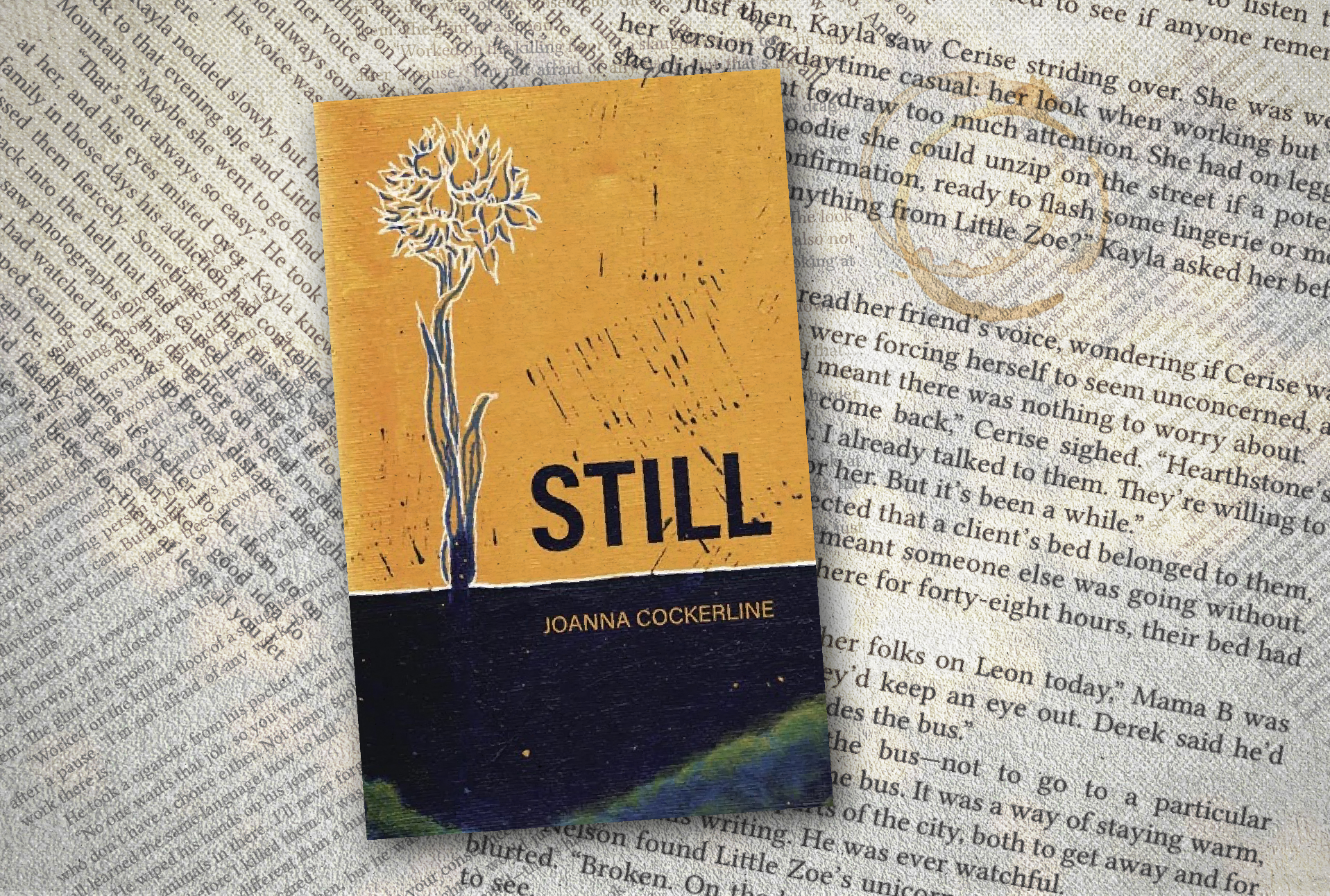

My journey of discovering what is really means to be Filipino-Canadian

By: Shekinah Natan

I grew up ashamed to be Filipino.

And no, it wasn’t because I was told to be ashamed or because I experienced overt racism (although that is the reality for many people). I was ashamed because I would hear my parents code-switching, a term used to describe when people of colour change or “switch” their style of speech to appear more professional. In the sense that I wasn’t taught Tagalog while I was growing up; that my sisters and I were subject to comments about our skin colour whenever we would spend a day in the sun. I never brought traditional Filipino food to school.

I, like many second-generation immigrants, was made to feel primitive or “FOB” – or Fresh off the Boat, a derogatory sentiment violently aimed at non-white communities who exist in predominantly white spaces– if we boasted about our culture and “whitewashed” if we did not know enough because we were forced to assimilate. See that’s the thing about living in western society: no matter how inclusionary or diverse they appear to be, you’re made aware of your differences and that’s when the erasure of culture, conscious and subconscious, begins

I hope through sharing my experiences growing up as a Filipino-Canadian, my relationship with my parents and how I was able to come to terms with my identity, can the realities of growing up as a second-generation immigrant be better understood as its own unique perspective.

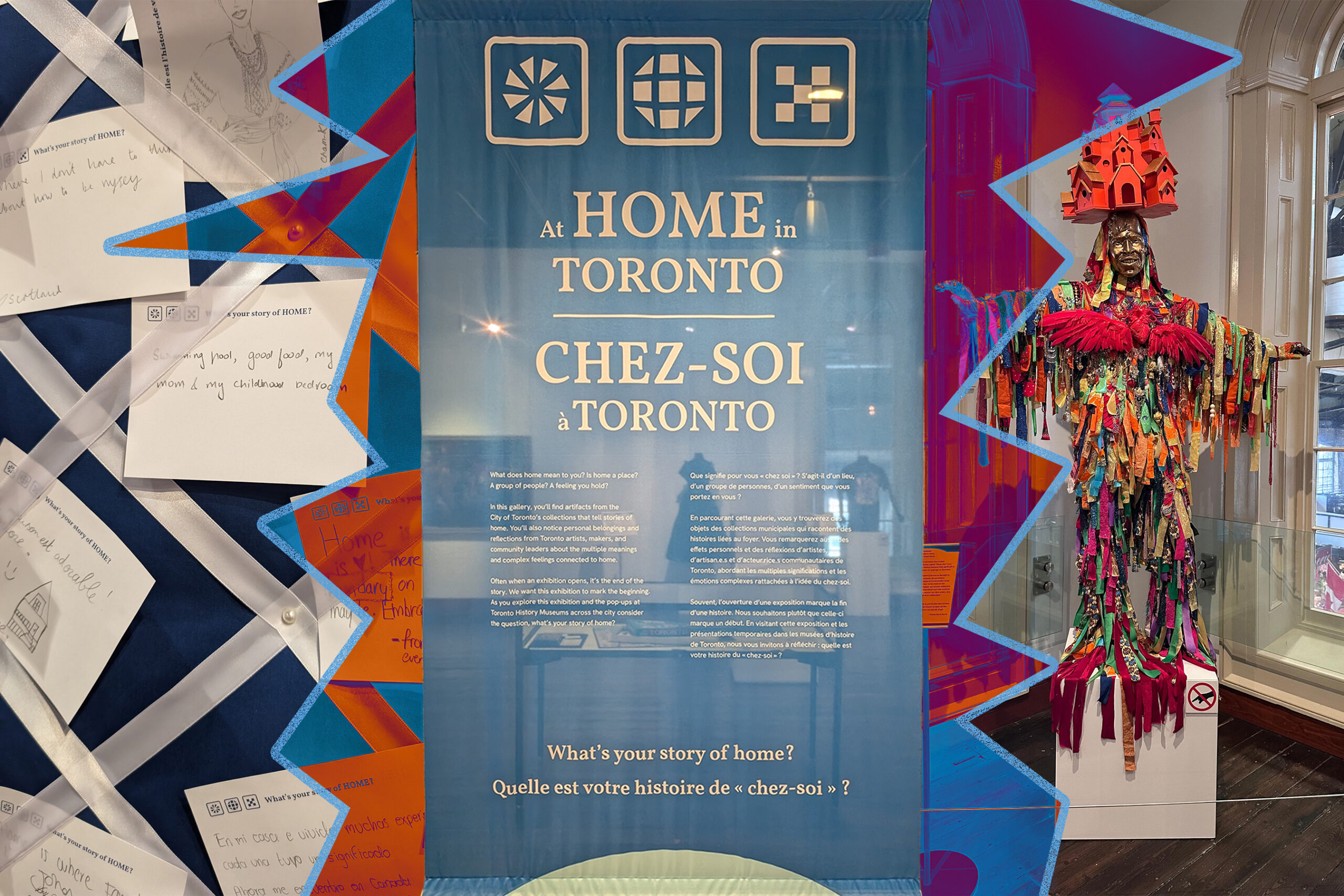

I grew up in Canada, a country where immigrants make up almost a quarter of its population, according to Statistics Canada. In fact, over 1.3 million new immigrants settled permanently in Canada, from 2016-2021. Immigrants are very much a part of the Canadian identity to say the least.

Despite growing up in Scarborough and attending a predominantly Filipino elementary school, I would often feel out of touch with my culture. A lot of the isolation I felt was due to societal pressures, especially from Eurocentric beauty standards that continue to torment women of colour today. I was always made aware of and thus insecure about my nose, my skin color and my body hair; aspects that helped define me as a Filipina.

On the other hand, I felt like an imposter– someone who was biologically Filipino and yet knew nothing about the culture. I felt envious of my friends whose parents would pack lunches with longaniza, adobo, rice and other traditional foods in Filipino culture. It was in these small ways that I felt like I was constantly hiding something.

I came to realize that unlike many of my friends, I did not have a huge extended family in Canada. Instead, much of my understanding of Filipino culture was limited to my parents and the fleeting moments when they would reminisce about the motherland. I realized just how uncommon it is to neither understand nor speak the language.

Unfortunately, growing up, no one told me how important it was to learn and be able to speak Tagalog, something I have and will always regret. The lack of knowledge I had and the inability to communicate with my relatives and other Filipinos were significant in my identity crisis growing up. This raises a big question for second generation immigrants and the lack of opportunity to practice their languages.

As second-generation immigrants, we try to navigate life with intense pressure to fit in, all the while trying to stay connected to our roots despite the overwhelming fear of being judged.

In a 2019 Calgary Journal article, reporter Karina Zapata cites assistant linguistics professor, Evangelia Daskalaki, who says that immigrant families are losing their heritage languages faster because of the minimal opportunities available for them to speak their mother tongue.

Daskalaki is also quoted saying, “[my students] discredit that this is their heritage, this is their whole foundation, and the more we learn about children, the more we learn about how important family and cultural identity is.” Language is a crucial link to our culture and our heritage but as Zapata mentions, immigrants and descendants of immigrants face many obstacles in preserving their cultural languages.

According to a 2016 census by Statistics Canada, 16.9 percent of immigrants are reported to only know English and 59.6 per cent to know English and at least one other language. Oftentimes I wished my parents could have done more and encouraged me to learn, but I now know my parents only stripped me of my ancestry out of necessity. To survive, they, along with my sister and I, had to conform to western society.

Like all children, we imitate our parents, their mannerisms and actions, whether we like to or not. In the case of second-generation immigrants, we carry our parents’ shame, regrets, hopes and dreams. It is very much in the immigrant mindset to struggle silently, to not cause a scene or draw attention and above all else, be “humble.”

I eventually realized the change of my parents’ voices in front of their bosses and colleagues was a silent message to me; that a Filipino accent was unprofessional. I would hear the conversations when my dad’s boss would talk down to him and all my dad could do was smile and apologize.

As their children, you resent how cruel the world is to the people who gave life to you; how it treats people who had to struggle to make it here and who gave up everything, all for you. So above all else, you want to make them proud. This shared need for parental validation among second-generation immigrants bears a childlike innocence but is more times than not, harmful. A lot of it has to do with intergenerational trauma, especially within immigrant families and their confined definition of success. This obligation to my parents and the fear of disappointing them held me back for a lot of my youth, especially from discovering what it is I truly want to achieve in this life.

Whenever I would talk about art school, my parents told me to keep it as a hobby and that there was no money in art and that my career options were limited to becoming a doctor, an engineer or a lawyer– an omnipresent diatribe heard universally by the children of immigrants. I came to realize that this was my parents’ way of staying in control, by projecting their aspirations onto me. They wanted to live vicariously through my sisters and me, who have the opportunities they wished they had growing up. This is a reason why I felt disconnected from my parents. However, I know now they are not entirely to blame, they did not grow up with the choices we have now. Because like many immigrant parents, it was and always will be about survival. This nuance in my parental relationship is partly why the second-generation immigrant experience is distinctively unique.

It took me a while to come to terms with my identity as a Filipino-Canadian and in many ways, I’m still figuring out what that means for me. My friends did, however, play a major role in that. Surrounding myself with people from the same background helped affirm and validate my identity as a Filipina, especially when it came to discussions about our upbringing. Having people who can understand your experience is extremely comforting, even if that comfort derives from small, stolen moments. Whether it’s through eating the same foods or hearing their parents speak the same language at home.

As I grew older, I met more of my extended family, having titas and titos (aunts and uncles for Filipinos) come over more often, I started to develop this sense of belonging that I once yearned for. This reconnection became more evident when my family and I would visit the Philippines. Being able to finally meet my cousins and experience the Philippines and its culture first-hand was moving. It was one of the first times I felt like I was a part of something bigger, that I had a community bound by blood. I would often wonder what my life would be like if my parents had never immigrated and sometimes I wish they hadn’t, solely due to the fact I would have been more connected to my Filipino roots. I was able to see what my parents’ life had been like before my sister, the homogeneousness of the Philippines compared to the multiculturalism seen in Canada and Toronto. Although I am grateful for the diversity in Canada and the privilege of being surrounded by rich cultures; I am lucky enough to be accustomed to people from different backgrounds and walks of life.

But despite the diversity around me, it took me a while to feel comfortable in my own skin and to genuinely be able to call myself Filipino. As second-generation immigrants, we try to navigate life with intense pressure to fit in, all the while trying to stay connected to our roots despite the overwhelming fear of being judged. We learn just how impossible it is to live up to our parents’ expectations and to overcome the image society has of immigrants. We grow up learning to suppress our struggles just as our parents did, and especially for people of color, we are numb to the lack of representation seen in the media and positions of influence and power. With time, the amount of second-generation immigrants will only increase. The percentage of second-generation Canadians under the age of 15 rose nearly five per cent in the last decade,, according to Statistics Canada.

Regardless of how society and the world continue to progress, there is still something that needs to be said about the mélange of the third culture experienced by Canadian children of immigrants. In the end, I was born Filipino and I will die Filipino, and no one can take that away from me, not even myself.