Photo via Pixabay

By Nadia Brophy

During the winter months, you may experience feelings of sadness, lack of energy and motivation and difficulty sleeping. You also may be quick to chalk these feelings up to a simple case of the “winter blues.”

However, modern research has shown that for some people, these fluctuations in mood and behaviour are indicative of a type of major clinical depression known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Those affected by SAD will often experience more severe symptoms including insomnia, anxiety, appetite changes and weight gain.

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), about 2 to 3 per cent of Canadians will experience SAD in their lifetime, as the disorder is more common in northern countries that are exposed to daylight for less time during the winter. SAD is thought to correlate with the seasonal changes in exposure to light and its effect on the body’s internal clock in knowing when to be active.

If you have been impacted by SAD or know someone who is currently being affected, have no fear, there is light at the end of the tunnel. Institutions across the country are doing their part to combat the prevalent disorder by making large-scale, therapeutic treatment methods accessible to the public.

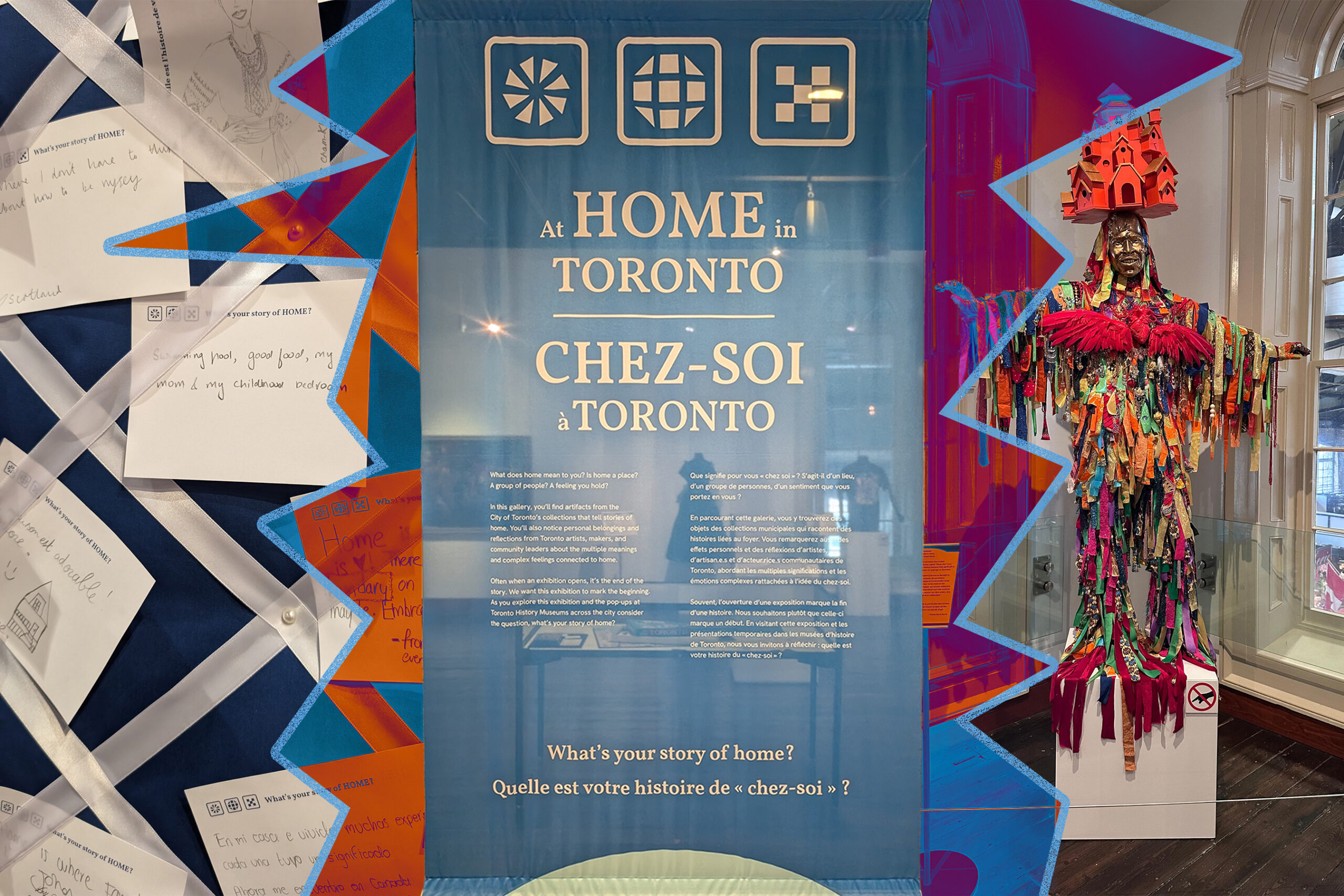

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Toronto has installed the Light Therapy exhibit, a singular room that is entirely white and doused in light from several sources, including multiple daylight-toned LEDs hanging from the ceiling and natural daylight that enters through three large windows. Controlled exposure to light is a common treatment prescribed to those affected by SAD as a way to reset the body’s internal clock to increase motivation and activity in patients. According to the CMHA, 60 to 80 per cent of people with SAD say light therapy helps alleviate their symptoms.

The interior of the Light Therapy room at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto. (CanCulture/Nadia Brophy)

The exhibit, created by Swedish architect and visual artist Apolonija Šušteršič, is part of the MOCA’s Art in Use project, which aims to use art in museums as a way to support public well-being and in the case of Light Therapy, to support mental health.

“The work is installed in the museum to discuss the potential for culture and art to improve happiness and well-being, as an art work and as a known therapy,” said November Paynter, the director of programs at the MOCA, in an email. “It also works to improve cognitive thinking and can be used as a meeting room and reading space to enhance thought and a place to gather and socialize and discuss.”

Socialization also plays an important role in the treatment of SAD to stimulate happiness and motivation, as according to the CMHA, it is common for affected individuals to avoid interacting with the people around them. At the Light Therapy exhibit, visitors are encouraged to talk among one another during their sessions.

Michael Bedford, a visitor at the exhibit, thinks Light Therapy is a step in the right direction for encouraging people with SAD to seek out treatment.

“I think when you have therapeutic methods like this, there’s a sense of community and there’s this breaking down of some of the stigma and silence around mental health,” said Bedford. “It’s more social motivation than it is individual-based therapy. People might be more willing to come to these things if they are looked at as a social activity.”

Libraries across Canada have also taken to the large-scale use of light therapy. It all began with Robin Mazumder, a PhD student in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Waterloo, who was inspired to help combat SAD after working as an occupational therapist in Edmonton treating people with mental health issues and noticing a change in his own mental health during the winter season.

Four years ago, Mazumder worked with the Edmonton Public Library to install three LED lamps used for light therapy in communal spaces around the building, launching Lightbrary, his project to promote country-wide accessibility to light therapy. According to Mazumder, the Lightbrary movement has reached several libraries across Canada since its launch, including in Toronto, Winnipeg and the Yukon.

Similar to the Light Therapy exhibit, Mazumder’s project also aims to not only expose the public to treatment methods, but also to promote the destigmatization of mental health.

“My goal was to start a conversation on mental health in general and have something to address the stigma of combating it in public spaces,” said Mazumder. “There’s a two-prong benefit to it; it’s accessing the lamps and getting people out of their homes.”

According to University Affairs, last year Mazumder took his mission to the University of Waterloo, filing a request for light therapy lamps to be installed on the campus to help prevent SAD from reaching the lives of students and to improve “campus life enhancement.”

“I just think that everyone should be able to access the lamps,” said Mazumder. “Students in general spend a lot of time inside at a computer and obviously the solution would be to have a better work-life balance, but that’s not reasonable for a lot of people for a number of reasons.”

According to Mazumder’s blog post on the Lightbrary website, he now turns his focus to working with Northern Light Technologies, the company he chooses to purchase the light therapy lamps from, to discount their lamps for other communities who wish to start their own Lightbrary initiative.

The Light Therapy exhibit at the MOCA is available for visit until April 30, 2019.